Gardens in war offer sustenance and solidarity. Defiance and subversion. While gardens and fields in Ukraine become bombsites and graveyards and farmers cannot plant or live, we garden through pandemic and war to replenish body and soul.

A famous story of Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s gardens in England shows Leonard's defiance. As WWII drew near, Virginia called for him to come inside to listen to "the lunatic" Hitler on the radio. Leonard shouted back:

“I shan’t come. I am planting iris, and they will be flowering long after he is dead.”

Gardeners today refer to this as an “Iris moment.”

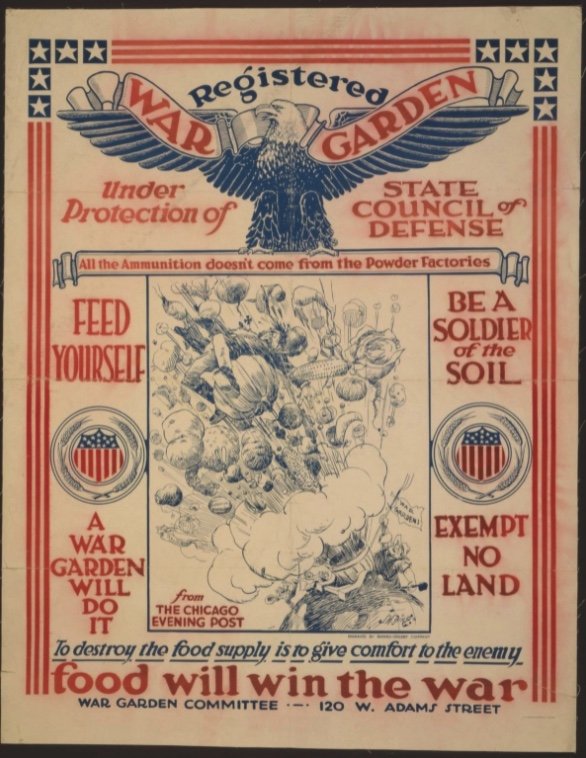

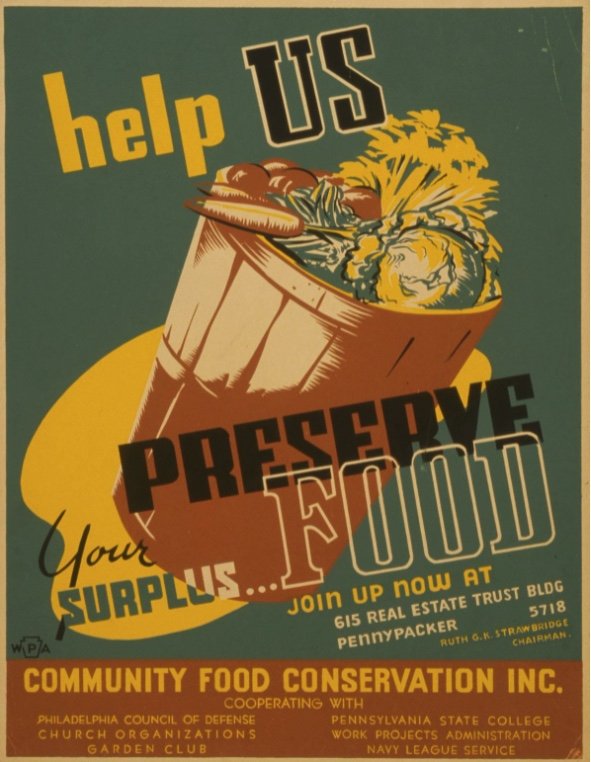

Food supplies felt the pressure of WWI and WWII. “War gardens,” as they were called in WWI, and “victory gardens” in WWII were supposed to take the strain off the dwindling food supply and boost morale. It was a way for the collective community to work together for the common good for “community and country.” Everyone had more than skin in the game – they had zucchini, eggplant, tomatoes, corn, peas, green beans, raspberries, blueberries and anything they could grow.

Backyards, churchyards, parks and playgrounds in the United States – and around the world – were full of fruits, vegetables and herbs. Their bounty supplemented rationing stamps or cards. These gardens became a source of pride and a way for anyone to contribute to the war effort. And gardeners got creative. One couple in England turned a bombsite into a garden.

Gardeners swapped seeds and news about their loved ones’ whereabouts and well-being.

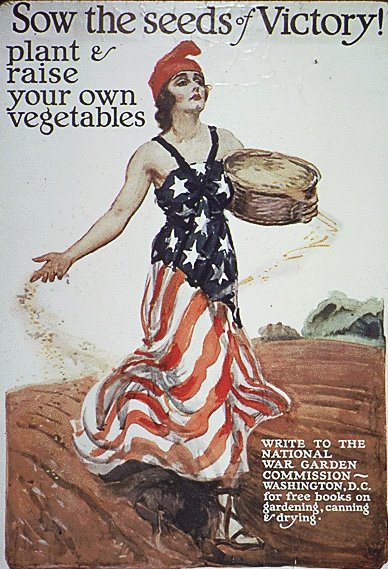

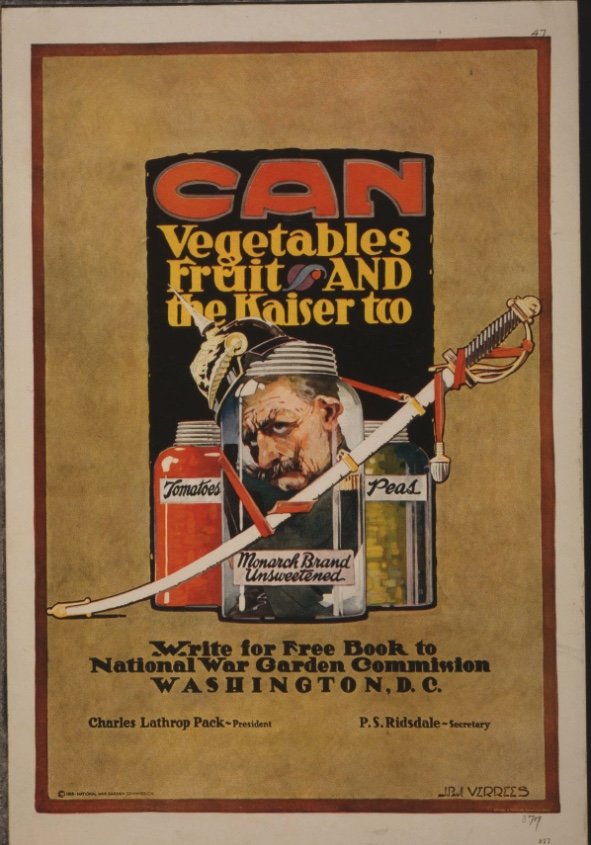

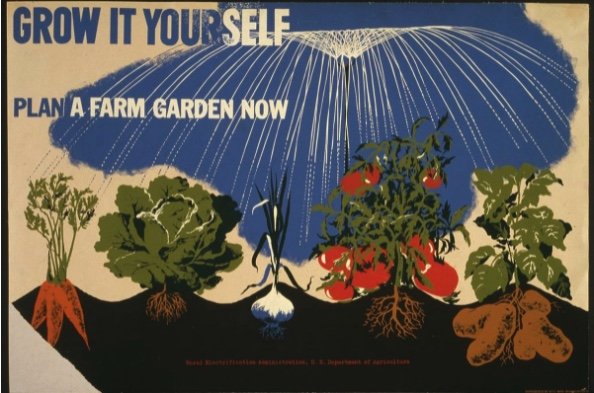

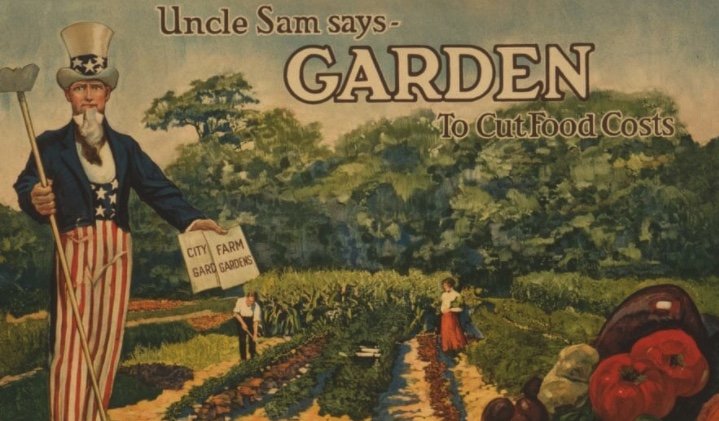

Posters promoting the Victory Garden were everywhere. In the U.S., a public service advertising campaign created by the National War Garden Commission encouraged everyone to do their part. Posters, magazine ads and newsreels touted the success of these local “victory gardens” with humor and pride. One poster showed a young boy with a hoe chasing fruits and vegetables over a hill. The headline: War Gardens Over the Hill – The Seeds of Victory Insure the Fruits of Peace.

This public service campaign also offered educational booklets and seeds. In today’s cluttered cyber market, with a clickbait rate of 10-15% considered successful, this public service campaign was record-breaking. Half of all households in America had a victory garden. And by the time the war ended in 1945, Americans had grown about eight million tons of food. That’s a lot of food.

My mother, born in 1936 in a small farming community in Minnesota, remembers collecting milkweed pods for the war effort – the silk was used in parachutes. And when she went to the movies, a newsreel promoted victory gardens.

And the war effort did something else.

It brought together diverse groups: government agencies, businesses, schools, churches. Corporate America played their part, too. Those victory gardens were underwritten by American companies that offered seeds with the purchase of their products. Sure, corporations got tax breaks and earned profits from their efforts, but their contribution added to the collective solidarity of a nation. My mother remembers the feeling that “everyone wanted to do their part and we were all in this together.”

For some, gardening is a subversive act: a way to thwart your dependence on large corporate farming. The idea being that every tomato you grow makes you less dependent on “big Agra,” as a fellow gardener told me. A close neighbor raises chickens in the center of town. Are they subversive chickens?

Ukraine, breadbasket of Europe, supplies wheat, corn and sunflowers. As fields lie fallow, who will pick up the slack?

My ancestors, who fled present-day Ukraine, cultivated the winter wheat that fed Russia. But when Russia revoked their promises, they were forced to leave because of “The Seeds of a Broken Promise.” My ancestors had their “Iris moment.” What will be our collective “iris moment”?

The sunflower is the national flower of Ukraine, and Ukrainian soldiers are being offered sunflower seeds so that when they die, sunflowers will sprout where they fall. Ukrainians know how to create solidarity and defiance in the darkness.

I intend to plant a lot of sunflowers. Let’s call it my “sunflower moment.”

Learn more about WWII Victory Gardens at the National Museum of American History https://gardens.si.edu/gardens/victory-garden/